Java 21 is Available Today, And It’s Quite the Update

Today’s the first day of Java 21’s availability! It’s been six months since Java 20 was released, so it’s time for another fresh wave of Java features. This post takes you on a tour of the JEPs that are associated with this release and it gives you a brief introduction to each of them. Where applicable the differences with Java 20 are highlighted and a few typical use cases are provided, so that you’ll be more than ready to use these features after reading this!

Image from PxHere

From Project Amber

Java 21 contains five features that originated from Project Amber:

- Pattern Matching for switch;

- Record Patterns;

- Unnamed Patterns and Variables;

- Unnamed Classes and Instance Main Methods;

- String Templates.

The goal of Project Amber is to explore and incubate smaller, productivity-oriented Java language features.

JEP 441: Pattern Matching for switch

The feature ‘Pattern Matching for switch’ (first introduced in Java 17) has reached completion status, now that Java 21 has been released.

Since Java 16 we’ve been able to avoid casting after instanceof checks by using ‘Pattern Matching for instanceof’. Let’s refresh our memory with a code example.

All code examples about Project Amber features were taken from my conference talk “Pattern Matching: Small Enhancement or Major Feature?”.

static String apply(Effect effect) {

String formatted = "";

if (effect instanceof Delay de) {

formatted = String.format("Delay active of %d ms.", de.timeInMs());

} else if (effect instanceof Reverb re) {

formatted = String.format("Reverb active of type %s and roomSize %d.", re.name(), re.roomSize());

} else if (effect instanceof Overdrive ov) {

formatted = String.format("Overdrive active with gain %d.", ov.gain());

} else if (effect instanceof Tremolo tr) {

formatted = String.format("Tremolo active with depth %d and rate %d.", tr.depth(), tr.rate());

} else if (effect instanceof Tuner tu) {

formatted = String.format("Tuner active with pitch %d. Muting all signal!", tu.pitchInHz());

} else {

formatted = String.format("Unknown effect active: %s.", effect);

}

return formatted;

}

This code is still riddled with ceremony, though. On top of that it leaves room for subtle bugs — what if you added an else-if branch that didn’t assign anything to formatted? Let’s see what pattern matching in a switch statement (or even better: in a switch expression) would look like:

static String apply(Effect effect) {

return switch(effect) {

case Delay de -> String.format("Delay active of %d ms.", de.timeInMs());

case Reverb re -> String.format("Reverb active of type %s and roomSize %d.", re.name(), re.roomSize());

case Overdrive ov -> String.format("Overdrive active with gain %d.", ov.gain());

case Tremolo tr -> String.format("Tremolo active with depth %d and rate %d.", tr.depth(), tr.rate());

case Tuner tu -> String.format("Tuner active with pitch %d. Muting all signal!", tu.pitchInHz());

case null, default -> String.format("Unknown or empty effect active: %s.", effect);

};

}

Pattern matching for switch made our code far more elegant here. We’re even able to address possible nulls by defining a specific case for them or combining it with the default case (which is what we’ve done here).

Checking an additional condition after the pattern match is easily done with a guard (the part after the when keyword in the code below):

static String apply(Effect effect, Guitar guitar) {

return switch(effect) {

case Delay de -> String.format("Delay active of %d ms.", de.timeInMs());

case Reverb re -> String.format("Reverb active of type %s and roomSize %d.", re.name(), re.roomSize());

case Overdrive ov -> String.format("Overdrive active with gain %d.", ov.gain());

case Tremolo tr -> String.format("Tremolo active with depth %d and rate %d.", tr.depth(), tr.rate());

case Tuner tu when !guitar.isInTune() -> String.format("Tuner active with pitch %d. Muting all signal!", tu.pitchInHz());

case Tuner tu -> "Guitar is already in tune.";

case null, default -> String.format("Unknown or empty effect active: %s.", effect);

};

}

Here, the guard makes sure that intricate boolean logic can still be expressed in a concise way. Having to nest if statements to test this logic within a case branch would not only be more verbose, but also potentially introduce subtle bugs that we set out to avoid in the first place.

What’s Different From Java 20?

There have been two major changes from the previous JEP:

- An earlier version of the ‘Pattern Matching for switch’ feature came with parenthesized patterns, which helped resolve parsing ambiguities back when guards were still expressed with the

&&operator. Now that thewhenkeyword has replaced the&&operator for guards, the value for parenthesized patterns has decreased significantly. So the choice was made to remove them in Java 21. - Switch expressions and statements now allow qualified enum constants as case constants. This makes it easier to do an exhaustive

switchon an interface type when both a class and an enum implementation of that interface exists. The JEP description has a good example of this mechanism, should you wish to learn more about it.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 441. Or if you want to try out pattern matching for switch with the provided code examples, then here’s a GitHub repository to get you started.

JEP 440: Record Patterns

With the introduction of record patterns, deconstructing records is now possible, along with nesting record and type patterns to enable a powerful, declarative, and composable form of data navigation and processing.

Records are transparent carriers for data. Code that receives an instance of a record will typically extract the data, known as the components. This was also the case in our ‘Pattern Matching for switch’ code example, if we assume that all implementations of the Effect interface were in fact records there. In that piece of code it is clear that the pattern variables only serve to access the record fields. Using record patterns we can avoid having to create pattern variables altogether:

static String apply(Effect effect) {

return switch(effect) {

case Delay(int timeInMs) -> String.format("Delay active of %d ms.", timeInMs);

case Reverb(String name, int roomSize) -> String.format("Reverb active of type %s and roomSize %d.", name, roomSize);

case Overdrive(int gain) -> String.format("Overdrive active with gain %d.", gain);

case Tremolo(int depth, int rate) -> String.format("Tremolo active with depth %d and rate %d.", depth, rate);

case Tuner(int pitchInHz) -> String.format("Tuner active with pitch %d. Muting all signal!", pitchInHz);

case null, default -> String.format("Unknown or empty effect active: %s.", effect);

};

}

Delay(int timeInMs) is a record pattern here, deconstructing the Delay instance into its components. And this mechanism can become even more powerful when we apply it to a more complicated object graph by using nested record patterns:

record Tuner(int pitchInHz, Note note) implements Effect {}

record Note(String note) {}

class TunerApplier {

static String apply(Effect effect, Guitar guitar) {

return switch(effect) {

case Tuner(int pitch, Note(String note)) -> String.format("Tuner active with pitch %d on note %s", pitch, note);

};

}

}

Inference of type arguments

Nested record patterns also benefit from inference of type arguments. For example:

class TunerApplier {

static String apply(Effect effect, Guitar guitar) {

return switch(effect) {

case Tuner(var pitch, Note(var note)) -> String.format("Tuner active with pitch %d on note %s", pitch, note);

};

}

}

Here the type arguments for the nested pattern Tuner(var pitch, Note(var note)) are inferred. This only works with nested patterns for now; type patterns do not yet support implicit inference of type arguments. So the type pattern Tuner tu is always treated as a raw type pattern.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Apart from some minor editorial changes and the fact that the feature is now in its final state, the main change since the second preview is the removal of support for record patterns appearing in the header of an enhanced for statement. Java 20 introduced this feature, but it was dropped in Java 21 because it “may need a significant redesign, to better align with other features under consideration” (see this OpenJDK ticket for more information). This may seem strange, but this is the way it can be with preview features: they are fully specified and implemented, and yet impermanent until the feature has been fully delivered. Not to worry though, JEP 440 also hints that support for record patterns in enhanced for statements may be re-proposed in a future JEP, presumably when it’s able to be better aligned with other features under consideration.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 440. Or if you want to try out record patterns with the provided code examples,, then here’s a GitHub repository to get you started.

JEP 443: Unnamed Patterns and Variables (Preview)

Data processing in Java has become increasingly streamlined since the introduction of records and record patterns. But in some cases writing out an entire record pattern when some record components aren’t even used in the logic that follows can be both cumbersome and confusing. Let’s consider the following code example:

static boolean isDelayTimeEqualToReverbRoomSize(EffectLoop effectLoop) {

if (effectLoop instanceof EffectLoop(Delay(int timeInMs), Reverb(String name, int roomSize))) {

return timeInMs == roomSize;

}

return false;

}

Here, the logic doesn’t reference the reverb name whatsoever, but Java currently doesn’t have a way to indicate this omission might be intentional. And so the entire record pattern has been written out, leading future readers of this code to doubt the correctness of the implementation.

Unnamed Patterns

JEP 443 proposes unnamed patterns, which could improve the situation here:

static boolean isDelayTimeEqualToReverbRoomSize(EffectLoop effectLoop) {

if (effectLoop instanceof EffectLoop(Delay(int timeInMs), Reverb(_, int roomSize))) {

return timeInMs == roomSize;

}

return false;

}

The underscore denotes the unnamed pattern here: it is an unconditional pattern which binds nothing. You can use it to indicate that it doesn’t matter to what first value the pattern matches the Reverb, as long as the second parameter can be matched to an int.

Unnamed Pattern Variables

Unnamed pattern variables are also proposed by this JEP. You can use them whenever you care about the type your record pattern will match, but when you don’t need any value bound to the pattern variable. Imagine we want our tuner code to also support tuning piano keys in the future, then we could use unnamed pattern variables like this:

static void apply(Effect effect, Piano piano) {

System.out.println(switch(effect) {

case Tuner(FlatNote _), Tuner(SharpNote _) -> "Tuning one of the black keys...";

case Tuner(RegularNote _) -> "Tuning one of the white keys...";

default -> "An unknown effect is active...";

});

}

Here, we execute specific logic when we encounter a tuner that tunes a flat (♭) or sharp (♯) note. We use an unnamed pattern variable, because the logic acts on the matched type only - the value can be safely ignored.

Unnamed Variables

Unnamed variables are useful in situations where variables are unused and their names are irrelevant, for example when keeping a counter variable within the body of a for-each loop:

int guitarCount = 0;

for (Guitar guitar : guitars) {

if (guitarCount < LIMIT) {

guitarCount++;

}

}

The guitar variable is declared and populated here, but it is never used. Unfortunately, its intentional non-use doesn’t come across as such to the reader. Moreover, static code analysis tools like Sonar will probably complain about the unused variable, raising suspicions even more. Introducing an unnamed variable can better convey the intent of the code:

int guitarCount = 0;

for (Guitar _ : guitars) {

if (guitarCount < LIMIT) {

guitarCount++;

}

}

Another good example could be handling exceptions in a generic way:

var lesPaul = new Guitar("Les Paul");

try {

cart.add(stock.get(lesPaul, guitarCount));

} catch (OutOfStockException _) {

System.out.println("Sorry, out of stock!");

}

Keep in mind that unnamed variables only make sense when they’re not visible outside a method, so they currently only work with local variables, exception parameters and lambda parameters. The theoretical concept of unnamed method parameters is briefly touched upon in the JEP, but supporting that comes with enough challenges to at least warrant postponing it to a future JEP.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Java 20 didn’t contain anything related to unnamed patterns and variables yet, so Java 21 is the first time we get to experiment with them. Note that the JEP is in the preview stage, so you’ll need to add the --enable-preview flag to the command-line to be able to take the feature for a spin.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 443.

JEP 445: Unnamed Classes and Instance Main Methods (Preview)

Java’s take on the classic Hello, World! program is notoriously verbose:

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

}

On top of that, it forces newcomers to Java to grasp a few concepts that they certainly don’t need on their first day of Java programming:

- The

publicaccess modifier and the role it plays in encapsulating units of code, together with its counterpartsprivate,protectedand default; - The

String[] argsparameter, that allows the operating system’s shell to pass arguments to the program; - The

staticmodifier and how it’s part of Java’s class-and-object model.

The motivation for this JEP is to help programmers that are new to Java by introducing concepts in the right order, starting with the more fundamental ones. This is done by hiding the unnecessary details until they are useful in larger programs.

Changing the Launch Protocol

To achieve this, the JEP proposes the following changes to the launch protocol:

- allow instance main methods, which are not

staticand don’t need apublicmodifier, nor aString[]parameter;

class HelloWorld {

void main() { // this is an instance main method

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

}

- introduce unnamed classes to make the

classdeclaration implicit;

void main() { // this is an instance main method inside of an unnamed class

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

Selecting a Main Method

In Java 21, when launching a class, the launch protocol chooses the first of the following methods to invoke:

- A

static void main(String[] args)method of non-private access (i.e.,public,protectedor package) declared in the launched class, - A

static void main()method of non-private access declared in the launched class, - A

void main(String[] args)instance method of non-private access declared in the launched class or inherited from a superclass, or, finally, - A

void main()instance method of non-private access declared in the launched class or inherited from a superclass.

Unnamed Classes

With the introduction of unnamed classes, the Java compiler will implicitly consider a method that is not enclosed in a class declaration, as well as any unenclosed fields and any classes declared in the file, to be members of an unnamed top-level class.

An unnamed class always belongs to the unnamed package, is final, and can’t implement interfaces or extend classes except Object. You can’t reference it by name or use method references for its static methods, but you can use this and make method references to its instance methods. Unnamed classes can’t be instantiated or referenced by name in code. They’re mainly used as program entry points and must have a main method, enforced by the Java compiler.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Java 20 didn’t contain anything related to unnamed classes and instance main methods yet, so Java 21 is the first time we get to experiment with them. Note that the JEP is in the preview stage, so you’ll need to add the --enable-preview flag to the command-line to be able to take the feature for a spin.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 445.

JEP 430: String Templates (Preview)

There are currently multiple ways in Java to compose a string from literal text and expressions:

- String concatenation with the

+operator; StringBuilder;String::formatorString::formatted;java.text.MessageFormat

However, these mechanisms come with drawbacks. They involve hard-to-read code (+ operator) or verbose code (StringBuilder), they separate the input string from the parameters (String::format) or they require a lot of ceremony (MessageFormat).

String interpolation is a mechanism that many programming languages offer as a solution to these drawbacks. But string interpolation comes with a drawback of its own: interpolated strings need to be manually validated by the developer to avoid dangerous risks like SQL injection.

This JEP proposes the ‘String Templates’ feature: a template-based mechanism for composing strings that offers the benefits of interpolation, but would be less prone to introducing security vulnerabilities. A template expression is a new kind of expression in Java, that can perform string interpolation but is also programmable in a way that helps developers compose strings safely and efficiently.

String guitarType = "Les Paul";

System.out.println(STR."I bought a \{guitarType} yesterday.");

// outputs "I bought a Les Paul yesterday."

The template expression STR."I bought a \{guitarType} yesterday." consists of:

- A template processor (

STR); - A dot character, as seen in other kinds of expressions; and

- A template (

"I bought a \{guitarType} yesterday.") which contains an embedded expression (\{guitarType}).

When a template expression is evaluated at run time, its template processor combines the literal text in the template with the values of the embedded expressions in order to produce a result. The embedded expressions can perform arithmetic, invoke methods and access fields:

int price = 12;

System.out.println(STR."A set of strings costs \{price} dollars; so each string costs \{price / 6} dollars.");

// outputs "A set of strings costs 12 dollars; so each string costs 2 dollars."

record Guitar(String name, boolean inTune) {}

class GuitarTuner {

public static void main(String... args) {

var guitar = new Guitar("Gibson Les Paul Standard '50s Heritage Cherry Sunburst", false);

System.out.println(STR."This guitar is \{guitar.inTune() ? "" : "not"} in tune.");

// outputs "This guitar is not in tune.

}

}

As you can see, double-quote characters can be used inside embedded expressions without escaping them as \", making the switch from concatenation (using +) to template expressions easier. Multi-line template expressions are also possible; they use a syntax similar to that of text blocks:

String title = "My Online Guitar Store";

String text = "Buy your next Les Paul here!";

String html = STR."""

<html>

<head>

<title>\{title}</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>\{text}</p>

</body>

</html>

""";

Template Processors

STR is a template processor defined in the Java Platform. It performs string interpolation by replacing each embedded expression in the template with the (stringified) value of that expression. It is a public static final field that is automatically imported into every Java source file.

More template processors exist:

FMT- besides performing interpolation, it also interprets format specifiers which appear to the left of embedded expressions. The format specifiers are the same as those defined injava.util.Formatter.RAW- a standard template processor that produces an unprocessedStringTemplateobject.

Ensuring Safety

The construct STR."..." we’ve used so far is actually a short way to define a template and call its process method. That means that our first code example:

String guitarType = "Les Paul";

System.out.println(STR."I bought a \{guitarType} yesterday.");

is equivalent to:

String guitarType = "Les Paul";

StringTemplate template = RAW."I bought a \{guitarType} yesterday.");

System.out.println(STR.process(template));

Template expressions are designed to prevent the direct conversion of strings with embedded expressions to interpolated strings. This makes it impossible for potentially incorrect strings to spread. A template processor securely handles this interpolation, and if you forget to use one, the compiler will report an error.

String guitarType = "Les Paul";

System.out.println("I bought a \{guitarType} yesterday."); // doesn't compile!

// outputs: "error: processor missing from template expression"

Custom Template Processors

Each template processor is an object that implements the functional interface StringTemplate.Processor, which means developers can easily create custom template processors. Custom template processors can make use of the methods StringTemplate::fragments and StringTemplate::values in order to use static fragments and dynamic values of the string template, respectively.

Custom template processors can be useful for various use cases. Let’s illustrate two of them with a few code examples:

var JSON = StringTemplate.Processor.of(

(StringTemplate st) -> new JSONObject(st.interpolate())

);

String name = "Gibson Les Paul Standard '50s Heritage Cherry Sunburst";

String type = "Les Paul";

JSONObject doc = JSON."""

{

"name": "\{name}",

"type": "\{type}"

};

""";

So the JSON template processor returns instances of JSONObject instead of String.

If we wanted, we could simply add more validation logic to the implementation of JSON to make the template processor handles its parameters a bit more safely.

record QueryBuilder(Connection conn) implements StringTemplate.Processor<PreparedStatement, SQLException> {

public PreparedStatement process(StringTemplate st) throws SQLException {

// 1. Replace StringTemplate placeholders with PreparedStatement placeholders

String query = String.join("?", st.fragments());

// 2. Create the PreparedStatement on the connection

PreparedStatement ps = conn.prepareStatement(query);

// 3. Set parameters of the PreparedStatement

int index = 1;

for (Object value : st.values()) {

switch (value) {

case Integer i -> ps.setInt(index++, i);

case Float f -> ps.setFloat(index++, f);

case Double d -> ps.setDouble(index++, d);

case Boolean b -> ps.setBoolean(index++, b);

default -> ps.setString(index++, String.valueOf(value));

}

}

return ps;

}

}

var DB = new QueryBuilder(conn);

String type = "Les Paul";

PreparedStatement ps = DB."SELECT * FROM Guitar g WHERE g.guitar_type = \{type}";

ResultSet rs = ps.executeQuery();

The DB custom template processor is capable of constructing PreparedStatements that have their parameters injected in a safe way.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Java 20 didn’t contain anything related to string templates yet, so Java 21 is the first time we get to experiment with them. Note that the JEP is in the preview stage, so you’ll need to add the --enable-preview flag to the command-line to be able to take the feature for a spin.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 430.

From Project Loom

Java 21 contains three features that originated from Project Loom:

- Virtual Threads;

- Structured Concurrency.

- Scoped Values;

Project Loom strives to simplify maintaining concurrent applications in Java by introducing virtual threads and an API for structured concurrency, among other things.

JEP 444: Virtual Threads

Threads have been a part of Java since the very beginning, and since the start of Project Loom we gradually started calling them ‘platform threads’ instead. A platform thread runs Java code on an underlying OS thread and captures the OS thread for the code’s entire lifetime. The number of platform threads is therefore limited to the number of available OS threads.

Modern applications, however, might need many more threads than that; when dealing with tens of thousands of requests at the same time, for example. This is where virtual threads come in. A virtual thread is an instance of java.lang.Thread that also runs Java code on an underlying OS thread, but does not capture the OS thread for the code’s entire lifetime. This means that many virtual threads can run their Java code on the same OS thread, effectively sharing it. The number of virtual threads can thus be much larger than the number of available OS threads.

Aside from being plentiful, virtual threads are also cheap to create and dispose of. This means that a web framework, for example, can dedicate a new virtual thread to the task of handling a request and still be able to process thousands or even millions of requests at once.

Typical Use Cases

Using virtual threads does not require learning new concepts, though it may require unlearning habits developed to cope with today’s high cost of threads. Virtual threads will not only help application developers; they will also help framework designers provide easy-to-use APIs that are compatible with the platform’s design without compromising on scalability.

Creating Virtual Threads

Just like a platform thread, a virtual thread is an instance of java.lang.Thread. So you can use a virtual thread in exactly the same way as a platform thread.

Creating a virtual thread is a bit different from creating a platform thread, but just as easy:

var platformThread = new Thread(() -> {

// do some work in a platform thread

});

platformThread.start();

var virtualThread = Thread.startVirtualThread(() -> {

// do some work in a virtual thread

});

When your code uses the ExecutorService interface already, switching to virtual threads will take even less effort:

var platformThreadsExecutor = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

platformThreadsExecutor.submit(() -> {

// do some work in a platform thread

});

platformThreadsExecutor.close();

try (var virtualThreadsExecutor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

virtualThreadsExecutor.submit(() -> {

// do some work in a virtual thread

});

} // close() is called implicitly

Note that the ExecutorService interface was adjusted in Java 19 to extend AutoCloseable, so it can now be used in a try-with-resources construct.

Thread Dump Mechanism

A new kind of thread dump in jcmd was introduced to present virtual threads alongside platform threads, all grouped in a meaningful way. This new way of presenting threads was needed, because of the way the JDK’s traditional thread dump (obtained through jstack or jcmd) presents a flat list of threads. The old format worked fine with hundreds of platform threads, but it is unsuitable for thousands or millions of virtual threads. An additional benefit of the new thread dump is the ability to show richer relationships amoung threads when programs use structured concurrency.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Based on developer feedback the following changes were made to virtual threads compared to Java 20:

- Virtual threads now always support thread-local variables. Guaranteed support for thread-local variables ensures that many more existing libraries can be used unchanged with virtual threads, and this helps with the migration of task-oriented code to use virtual threads.

- Virtual threads created directly with the Thread.Builder API (as opposed to those created through

Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) are now also, by default, monitored throughout their lifetime and observable via the new thread dump mechanism.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 444.

JEP 453: Structured Concurrency (Preview)

Java’s current implementation of concurrency is unstructured, meaning that tasks run independently of each other. They don’t come with any hierarchy, scope, or other structure, which means they cannot easily pass errors or cancellation intent to each other. To illustrate this, let’s look at a code example that takes place in a restaurant:

All code examples that illustrate Structured Concurrency were taken from my conference talk “Java’s Concurrency Journey Continues! Exploring Structured Concurrency and Scoped Values”.

public class MultiWaiterRestaurant implements Restaurant {

@Override

public MultiCourseMeal announceMenu() throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

Waiter grover = new Waiter("Grover");

Waiter zoe = new Waiter("Zoe");

Waiter rosita = new Waiter("Rosita");

try (var executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

Future<Course> starter = executor.submit(() -> grover.announceCourse(CourseType.STARTER));

Future<Course> main = executor.submit(() -> zoe.announceCourse(CourseType.MAIN));

Future<Course> dessert = executor.submit(() -> rosita.announceCourse(CourseType.DESSERT));

return new MultiCourseMeal(starter.get(), main.get(), dessert.get());

}

}

}

Now, consider the fact that the announceCourse(..) method in the Waiter class sometimes fails with an OutOfStockException, because one of the ingredients for the course might not be in stock. This can lead to some problems:

- If

zoe.announceCourse(CourseType.MAIN)takes a long time to execute butgrover.announceCourse(CourseType.STARTER)fails in the meantime, theannounceMenu(..)method will unnecessarily wait for the main course announcement by blocking onmain.get(), instead of cancelling it (which would be the sensible thing to do). - If an exception happens in

zoe.announceCourse(CourseType.MAIN),main.get()will throw it, butgrover.announceCourse(CourseType.STARTER)will continue to run in its own thread, resulting in thread leakage. - If the thread executing

announceMenu(..)is interrupted, the interruption will not propagate to the subtasks: all threads that run anannounceCourse(..)invocation will leak, continuing to run even afterannounceMenu()has failed.

Ultimately the problem here is that our program is logically structured with task-subtask relationships, but these relationships exist only in the mind of the developer. We might all prefer structured code that reads like a sequential story, but this example simply doesn’t meet that criterion.

In contrast, the execution of single-threaded code always enforces a hierarchy of tasks and subtasks. Consider the following single-threaded version of our restaurant example:

public class SingleWaiterRestaurant implements Restaurant {

@Override

public MultiCourseMeal announceMenu() throws OutOfStockException {

Waiter elmo = new Waiter("Elmo");

Course starter = elmo.announceCourse(CourseType.STARTER);

Course main = elmo.announceCourse(CourseType.MAIN);

Course dessert = elmo.announceCourse(CourseType.DESSERT);

return new MultiCourseMeal(starter, main, dessert);

}

}

Here, we don’t have any of the problems we had before. Our waiter Elmo will announce the courses in exactly the right order, and if one subtask fails the remaining one(s) won’t even be started. And because all work runs in the same thread, there is no risk of thread leakage.

So from these two examples it is evident that concurrent programming would be a lot easier and more intuitive if it would be able to enforce the hierarchy of tasks and subtasks, just like single-threaded code can.

Introducing Structured Concurrency

In a structured concurrency approach, threads have a clear hierarchy, their own scope, and clear entry and exit points. Structured concurrency arranges threads hierarchically, akin to function calls, forming a tree with parent-child relationships. Execution scopes persist until all child threads complete, matching code structure.

Shutdown on Failure

Let’s now take a look at a structured, concurrent version of our example:

public class StructuredConcurrencyRestaurant implements Restaurant {

@Override

public MultiCourseMeal announceMenu() throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

Waiter grover = new Waiter("Grover");

Waiter zoe = new Waiter("Zoe");

Waiter rosita = new Waiter("Rosita");

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

Supplier<Course> starter = scope.fork(() -> grover.announceCourse(CourseType.STARTER));

Supplier<Course> main = scope.fork(() -> zoe.announceCourse(CourseType.MAIN));

Supplier<Course> dessert = scope.fork(() -> rosita.announceCourse(CourseType.DESSERT));

scope.join(); // 1

scope.throwIfFailed(); // 2

return new MultiCourseMeal(starter.get(), main.get(), dessert.get()); // 3

}

}

}

The scope’s purpose is to keep the threads together.

At 1, we wait (join) until all threads are done with their work.

If one of the threads is interrupted, an InterruptedException is thrown here.

At 2, an ExecutionException can be thrown if an exception occurs in one of the threads.

Once we reach 3, we can be sure everything has gone well, and we can retrieve and process the results.

Actually, the main difference with the code we had before is the fact that we create threads (fork) within a new scope.

Now we can be certain that the lifetimes of the three threads are confined to this scope, which coincides with the body of the try-with-resources statement.

Furthermore, we’ve gained short-circuiting behaviour.

When one of the announceCourse(..) subtasks fails, the others are cancelled if they have not completed yet.

This behaviour is managed by the ShutdownOnFailure policy.

We’ve also gained cancellation propagation.

When the thread that runs announceMenu() is interrupted before or during the call to scope.join(), all subtasks are cancelled automatically when the thread exits the scope.

Shutdown on Success

A shutdown-on-failure policy cancels tasks if one of them fails, while a shutdown-on-success policy cancels tasks if one succeeds. The latter is useful to prevent unnecessary work once a successful result is obtained.

Let’s see what a shutdown-on-success implementation would look like:

public record DrinkOrder(Guest guest, Drink drink) {}

public class StructuredConcurrencyBar implements Bar {

@Override

public DrinkOrder determineDrinkOrder(Guest guest) throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException {

Waiter zoe = new Waiter("Zoe");

Waiter elmo = new Waiter("Elmo");

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnSuccess<DrinkOrder>()) {

scope.fork(() -> zoe.getDrinkOrder(guest, BEER, WINE, JUICE));

scope.fork(() -> elmo.getDrinkOrder(guest, COFFEE, TEA, COCKTAIL, DISTILLED));

return scope.join().result(); // 1

}

}

}

In this example the waiter is responsible for getting a valid DrinkOrder object based on the preferences of the guest and the current supply of drinks at the bar.

After the method Waiter.getDrinkOrder(Guest guest, DrinkCategory... categories) has been called, the waiter starts to list all available drinks in the drink categories that were passed to the method.

Once a guest hears something they like, they respond and the waiter creates a drink order. When this happens, the getDrinkOrder(..) method returns a DrinkOrder object and the scope will shut down.

This means that any unfinished subtasks (such as the one in which Elmo is still listing different kinds of tea) will be cancelled.

The result() method at 1 will either return a valid DrinkOrder object, or throw an ExecutionException if one of the subtasks has failed.

Custom Shutdown Policies

Two shutdown policies are provided out-of-the-box, but it’s also possible to create your own by extending the class StructuredTaskScope and its protected handleComplete(..) method.

That will allow you to have full control over when the scope will shut down and what results will be collected.

What’s Different From Java 20?

The situation is roughly the same as how it was in Java 20 (see JEP 437), except for two minor changes:

- Structured Concurrency is now a Preview API;

- The

StructuredTaskScope::forkmethod now returns aSubtaskinstead of aFuture(why?).

Note that the JEP is in the preview stage, so you’ll need to add the --enable-preview flag to the command-line to be able to take the feature for a spin.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 453. Or if you want to try out structured concurrency and you liked the code examples, then here’s a GitHub repository to get you started.

JEP 446: Scoped Values (Preview)

Scoped values enable the sharing of immutable data within and across threads. They are preferred to thread-local variables, especially when using large numbers of virtual threads.

ThreadLocal

Since Java 1.2 we can make use of ThreadLocal variables, which confine a certain value to the thread that created it. Back then it could be a simple way to achieve thread-safety, in some cases.

But thread-local variables also come with a few caveats. Every thread-local variable is mutable, which makes it hard to discern which component updates shared state and in what order. There’s also the risk of memory leaks, because unless you call remove() on the ThreadLocal the data is retained until it is garbage collected (which is only after the thread terminates). And finally, thread-local variables of a parent thread can be inherited by child threads, which results in the child thread having to allocate storage for every thread-local variable previously written in the parent thread.

These drawbacks become more apparent now that virtual threads have been introduced, because millions of them could be active at the same time - each with their own thread-local variables - which would result in a significant memory footprint.

Scoped Values

Like a thread-local variable, a scoped value has multiple incarnations, one per thread. Unlike a thread-local variable, a scoped value is written once and is then immutable, and is available only for a bounded period during execution of the thread.

The JEP illustrates the use of scoped values with the pseudo code example below:

final static ScopedValue<...> V = ScopedValue.newInstance();

// In some method

ScopedValue.where(V, <value>)

.run(() -> { ... V.get() ... call methods ... });

// In a method called directly or indirectly from the lambda expression

... V.get() ...

We see that ScopedValue.where(...) is called, presenting a scoped value and the object to which it is to be bound. The call to run(...) binds the scoped value, providing an incarnation that is specific to the current thread, and then executes the lambda expression passed as argument. During the lifetime of the run(...) call, the lambda expression, or any method called directly or indirectly from that expression, can read the scoped value via the value’s get() method. After the run(...) method finishes, the binding is destroyed.

Typical Use Cases

Scoped values will be useful in all places where currently thread-local variables are used for the purpose of one-way transmission of unchanging data.

What’s Different From Java 20?

The only difference from Java 20 is that Scoped Values has become a Preview API in Java 21, which means you’ll need to add the --enable-preview flag to the command-line to be able to take the feature for a spin.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 446.

From Project Panama

Java 21 contains two features that originated from Project Panama:

- Foreign Function & Memory API;

- Vector API.

Project Panama aims to improve the connection between the JVM and foreign (non-Java) libraries.

JEP 442: Foreign Function & Memory API (Third Preview)

Java programs have always had the option of interacting with code and data outside of the Java runtime, through the Java Native Interface (JNI). And accessing foreign memory (outside of the JVM, so off-heap) was possible using either the ByteBuffer API or the sun.misc.Unsafe API.

However, all these mechanisms have downsides, which is why a more modern API is now proposed to support foreign functions and foreign memory in a better way.

Performance-critical libraries like Tensorflow, Lucene or Netty typically rely on using foreign memory, because they need more control over the memory they use to prevent the cost and unpredictability that comes with garbage collection.

Code Example

In order to demonstrate the new API, JEP 442 lists a code example that obtains a method handle for a C library function radixsort and then uses it to sort four strings that start out as Java array elements:

// 1. Find foreign function on the C library path

Linker linker = Linker.nativeLinker();

SymbolLookup stdlib = linker.defaultLookup();

MethodHandle radixsort = linker.downcallHandle(stdlib.find("radixsort"), ...);

// 2. Allocate on-heap memory to store four strings

String[] javaStrings = { "mouse", "cat", "dog", "car" };

// 3. Use try-with-resources to manage the lifetime of off-heap memory

try (Arena offHeap = Arena.ofConfined()) {

// 4. Allocate a region of off-heap memory to store four pointers

MemorySegment pointers = offHeap.allocateArray(ValueLayout.ADDRESS, javaStrings.length);

// 5. Copy the strings from on-heap to off-heap

for (int i = 0; i < javaStrings.length; i++) {

MemorySegment cString = offHeap.allocateUtf8String(javaStrings[i]);

pointers.setAtIndex(ValueLayout.ADDRESS, i, cString);

}

// 6. Sort the off-heap data by calling the foreign function

radixsort.invoke(pointers, javaStrings.length, MemorySegment.NULL, '\0');

// 7. Copy the (reordered) strings from off-heap to on-heap

for (int i = 0; i < javaStrings.length; i++) {

MemorySegment cString = pointers.getAtIndex(ValueLayout.ADDRESS, i);

javaStrings[i] = cString.getUtf8String(0);

}

} // 8. All off-heap memory is deallocated here

assert Arrays.equals(javaStrings, new String[] {"car", "cat", "dog", "mouse"}); // true

Let’s look at some of the types this code uses in more detail to get a rough idea of their function and purpose within the Foreign Function & Memory API:

Linker- Provides access to foreign functions from Java code, and access to Java code from foreign functions. It allows Java code to link against foreign functions, via downcall method handles. It also allows foreign functions to call Java method handles, via the generation of upcall stubs. See the JavaDoc of this type for more information.

SymbolLookup- Retrieves the address of a symbol in one or more libraries. See the JavaDoc of this type for more information.

Arena- Controls the lifecycle of memory segments. An arena has a scope, called the arena scope. When the arena is closed, the arena scope is no longer alive. As a result, all the segments associated with the arena scope are invalidated, their backing memory regions are deallocated (where applicable) and can no longer be accessed after the arena is closed. See the JavaDoc of this type for more information.

MemorySegment- Provides access to a contiguous region of memory. There are two kinds of memory segments: heap segments (inside the Java memory heap) and native segments (outside of the Java memory heap). See the JavaDoc of this type for more information.

ValueLayout- Models values of basic data types, such as integral values, floating-point values and address values. On top of that, it defines useful value layout constants for Java primitive types and addresses. See the JavaDoc of this type for more information.

What’s Different From Java 20?

In Java 20, this feature was in second preview (in the form of JEP 434) to gather more developer feedback. Based on this feedback the following changes happened in Java 21:

- Lifetimes management of native segments in the

Arenainterface is now centralized; - Layout paths with a new element to dereference address layouts have been enhanced;

- A linker option to optimize calls to functions that are short-lived and will not upcall to Java has been provided;

- A fallback native linker implementation has been provided, to facilitate porting;

- The

VaListclass has been removed.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 442.

JEP 448: Vector API (Sixth Incubator)

The Vector API makes it possible to express vector computations that reliably compile at runtime to optimal vector instructions. This means that these computations will significantly outperform equivalent scalar computations on the supported CPU architectures (x64 and AArch64).

Vector Computations? Help Me Out Here!

A vector computation is a mathematical operation on one or more one-dimensional matrices of an arbitrary length. Think of a vector as an array with a dynamic length. Furthermore, the elements in the vector can be accessed in constant time via indices, just like with an array.

In the past, Java programmers could only program such computations at the assembly-code level. But now that modern CPUs support advanced SIMD features (Single Instruction, Multiple Data), it becomes more important to take advantage of the performance gains that SIMD instructions and multiple lanes operating in parallel can bring. The Vector API brings that possibility closer to the Java programmer.

Code Example

Here is a code example (taken from the JEP) that compares a simple scalar computation over elements of arrays with its equivalent using the Vector API:

void scalarComputation(float[] a, float[] b, float[] c) {

for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

c[i] = (a[i] * a[i] + b[i] * b[i]) * -1.0f;

}

}

static final VectorSpecies<Float> SPECIES = FloatVector.SPECIES_PREFERRED;

void vectorComputation(float[] a, float[] b, float[] c) {

int i = 0;

int upperBound = SPECIES.loopBound(a.length);

for (; i < upperBound; i += SPECIES.length()) {

// FloatVector va, vb, vc;

var va = FloatVector.fromArray(SPECIES, a, i);

var vb = FloatVector.fromArray(SPECIES, b, i);

var vc = va.mul(va)

.add(vb.mul(vb))

.neg();

vc.intoArray(c, i);

}

for (; i < a.length; i++) {

c[i] = (a[i] * a[i] + b[i] * b[i]) * -1.0f;

}

}

From the perspective of the Java developer, this is just another way of expressing scalar computations. It might come across as being more verbose, but on the other hand it can bring spectacular performance gains.

Typical Use Cases

The Vector API provides a way to write complex vector algorithms in Java that perform extremely well, such as vectorized hashCode implementations or specialized array comparisons. Numerous domains can benefit from this, including machine learning, linear algebra, encryption, text processing, finance, and code within the JDK itself.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Aside from a minor set of enhancements in the API, the biggest differences with Java 20 are:

- Add the exclusive or (xor) operation to vector masks.

- Improve the performance of vector shuffles, especially when used to rearrange the elements of a vector and when converting between vectors.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 448.

HotSpot

Java 21 introduces three changes to HotSpot:

- Generational ZGC;

- Deprecate the Windows 32-bit x86 Port for Removal;

- Prepare to Disallow the Dynamic Loading of Agents.

The HotSpot JVM is the runtime engine that is developed by Oracle. It translates Java bytecode into machine code for the host operating system’s processor architecture.

JEP 439: Generational ZGC

The Z Garbage Collector (ZGC) is a scalable, low-latency garbage collector. It has been available for production use since Java 15 and has been designed to keep pause times consistent and short, even for very large heaps. It uses techniques like region-based memory management and compaction to achieve this.

Java 21 introduces an extension to ZGC that maintains separate generations for young and old objects, allowing ZGC to collect young objects (which tend to die young) more frequently. This will result in a significant performance gain for applications running with generational ZGC, without sacrificing any of the valuable properties that the Z garbage collector is already known for:

- Pause times do not exceed 1 millisecond;

- Heap sizes from a few hundred megabytes up to many terabytes are supported;

- Minimal manual configuration is needed.

The reason for handling young and old objects separately stems from the weak generational hypothesis, stating that young objects tend to die young, while old objects tend to stick around. This means that collecting young objects requires fewer resources and yields more memory, while collecting old objects requires more resources and yields less memory. This is the reason we can improve the performance of applications that use ZGC by collecting young objects more frequently.

What’s Different From Java 20?

The Z garbage collector in Java 20 was only able to behave in a non-generational way. Running it required the following command-line configuration:

$ java -XX:+UseZGC ...

To run your workload with the new Generational ZGC in Java 21, use the following configuration:

$ java -XX:+UseZGC -XX:+ZGenerational ...

As you can see, Generational ZGC has been introduced alongside non-generational ZGC. In a future release we can expect Generational ZGC to become the default configuration for the Z garbage collector, while an even later release will probably remove non-generational ZGC altogether.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 439.

JEP 449: Deprecate the Windows 32-bit x86 Port for Removal

Supporting multiple platforms has been the focus of the Java ecosystem since the beginning. But older platforms cannot be supported indefinitely, and that is one of the reasons why the Windows 32-bit x86 port is now scheduled for removal.

There are a few reasons for this:

- Windows 10, the last Windows operating system to support 32-bit operation, will reach end-of-life in October 2025;

- The implementation of virtual threads on Windows 32-bit x86 is rudimentary to say the least: it uses a single platform thread for each virtual thread, effectively rendering the feature useless on this platform;

- It will allow the OpenJDK contributors to accelerate the development of new features and enhancements.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Configuring a Windows x86-32 build will now fail on JDK 21.

This error can be suppressed by using the new build configuration option --enable-deprecated-ports=yes.

This means Windows x86-32 users can still use JDK 21; however a future release will actually remove the support, and by that time the affected users are expected to have migrated to Windows x64 and a 64-bit JVM.

More Information

For more information about this deprecation, see JEP 449.

JEP 451: Prepare to Disallow the Dynamic Loading of Agents

An agent is a component that can alter the code of a Java application while it is running. Introduced in JDK 5, agents provide a way for tools (such as profilers) to instrument classes, with the aim of altering the code in a class so that it emits events to be consumed by a tool outside the application. Dynamically loaded agents grant serviceability tools the capability to modify a running application. However, this capability is available to both tools and libraries, and it can just as easily be used for modifications with bad intentions. To assure integrity, stronger measures are needed to prevent the misuse by libraries of dynamically loaded agents. JEP 451 therefore proposes to require the dynamic loading of agents to be approved by the application owner. This means that in Java 21, the application owner will have to explicitly allow the dynamic loading of agents via a command-line option.

What’s Different From Java 20?

Java 21 is the first version of Java that issues warnings when agents are loaded dynamically into a running JVM. A future release of the JDK will, by default, disallow the mechanism. Agents that are loaded at startup will still be allowed though, so serviceability tools that use that mechanism won’t be affected now or in the future. Maintainers of libraries which rely on dynamically agent loading will have to update their documentation to ask application owners for permission to load the agent at startup.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 451.

Core & Security Libs

Java 21 also brings you two additions that are part of the Core Libs and Security Libs, respectively:

- Sequenced Collections

- Key Encapsulation Mechanism API

JEP 431: Sequenced Collections

One of the most well-known APIs in Java is the collections framework, but did you know it doesn’t even contain a collection type that represents an ordered sequence of elements? Sure, there are some subtypes that support encounter order (such as List, SortedSet and Deque), but their common supertype is Collection, which does not support it. So support for encounter order is dispersed across the type hierarchy, and that leads to more challenges. Consider obtaining the first or last element of a collection, for instance. While numerous implementations accommodate this functionality, each adopts a distinct approach, and a few are not as obvious (or don’t support it at all). The process of sequentially traversing collection elements from the beginning to the end might appear simple and systematic, but iterating in reverse order is notably less straightforward.

It seems like the concept of a collection with defined encounter order exists in multiple places in the collections framework, but there is no single type that represents it. And this is the gap in the collections framework that will be filled by Sequenced Collections.

New Interfaces

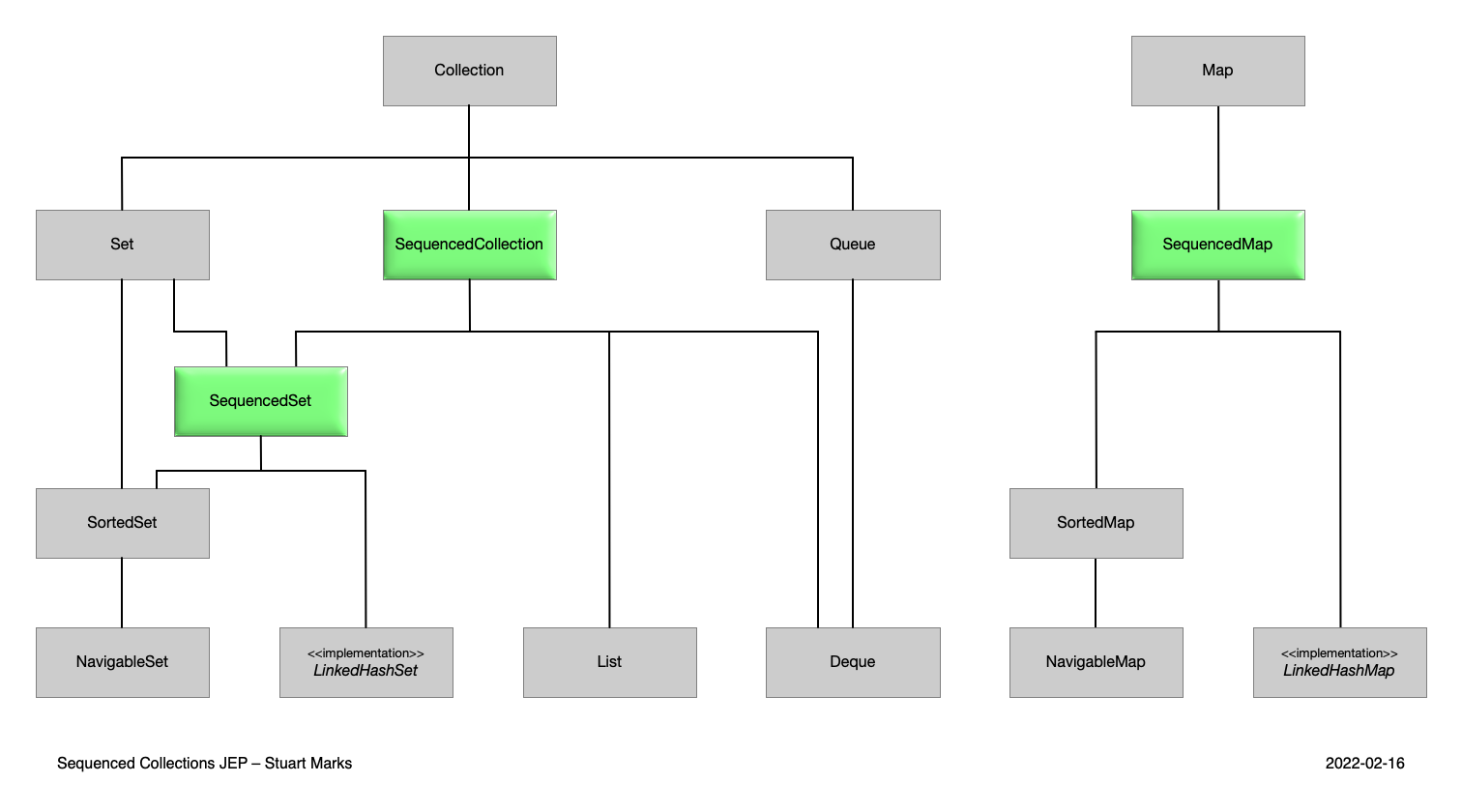

The JEP will introduce new interfaces for sequenced collections, sequenced sets and sequenced maps. They are retrofitted into the existing collections type hierarchy (making ample use of default methods), as follows:

Image from JEP 431

A sequenced collection has first and last elements, allowing support for common operations at either end:

interface SequencedCollection<E> extends Collection<E> {

// new method

SequencedCollection<E> reversed();

// methods promoted from Deque

void addFirst(E);

void addLast(E);

E getFirst();

E getLast();

E removeFirst();

E removeLast();

}

A sequenced set is a Set that is a SequencedCollection that contains no duplicate elements:

interface SequencedSet<E> extends Set<E>, SequencedCollection<E> {

SequencedSet<E> reversed(); // covariant override

}

A sequenced map is a Map whose entries have a defined encounter order:

interface SequencedMap<K,V> extends Map<K,V> {

// new methods

SequencedMap<K,V> reversed();

SequencedSet<K> sequencedKeySet();

SequencedCollection<V> sequencedValues();

SequencedSet<Entry<K,V>> sequencedEntrySet();

V putFirst(K, V);

V putLast(K, V);

// methods promoted from NavigableMap

Entry<K, V> firstEntry();

Entry<K, V> lastEntry();

Entry<K, V> pollFirstEntry();

Entry<K, V> pollLastEntry();

}

The Collections utility class has also been extended to create unmodifiable wrappers for the three new types:

Collections.unmodifiableSequencedCollection(sequencedCollection)Collections.unmodifiableSequencedSet(sequencedSet)Collections.unmodifiableSequencedMap(sequencedMap)

What’s Different From Java 20?

Java 20 didn’t contain anything related to sequenced collections yet, so everything that you read about it so far is as new as it gets! However, the feature that now has been delivered is the result of an incremental evolution of an earlier proposal called reversible collections. And if you’re up for a trip down memory lane: the earliest form of this proposal was the one by Tagir Valeev’s from 2020 called OrderedMap/OrderedSet. These proposals have played a big part in shaping the feature that is now called ‘sequenced collections’ and that we get to enjoy in Java 21.

More Information

For more information on this feature, see JEP 431.

JEP 452: Key Encapsulation Mechanism API

A protocol like Transport Layer Security (TLS) relies heavily on public key encryption schemes in order to provide a secure way for a sender and recipient to share information. But public key encryption schemes are usually less efficient than symmetric encryption schemes, which instead focus on establishing a shared symmetric key as the basis of all future communication between sender and recipient. Such a key is typically produced by a key encapsulation mechanism (or KEM), and JEP 452 proposes to introduce an API for it.

Components

A KEM needs the following components:

- a key pair generation function that returns a key pair containing a public key and a private key.

This function is already covered by the existing

KeyPairGeneratorAPI.

- a key encapsulation function, called by the sender, that takes the receiver’s public key and an encryption option; it returns a secret key and a ciphertext. The sender sends the key encapsulation message to the receiver.

The new

KEMclass contains an encapsulation function.

- a key decapsulation function, called by the receiver, that takes the receiver’s private key and the received key encapsulation message; it returns the secret key.

The new

KEMclass contains a decapsulation function.

KEM class

For illustration purposes, the KEM class that is mentioned in the JEP is listed below:

package javax.crypto;

public class DecapsulateException extends GeneralSecurityException;

public final class KEM {

public static KEM getInstance(String alg)

throws NoSuchAlgorithmException;

public static KEM getInstance(String alg, Provider p)

throws NoSuchAlgorithmException;

public static KEM getInstance(String alg, String p)

throws NoSuchAlgorithmException, NoSuchProviderException;

public static final class Encapsulated {

public Encapsulated(SecretKey key, byte[] encapsulation, byte[] params);

public SecretKey key();

public byte[] encapsulation();

public byte[] params();

}

public static final class Encapsulator {

String providerName();

int secretSize(); // Size of the shared secret

int encapsulationSize(); // Size of the key encapsulation message

Encapsulated encapsulate();

Encapsulated encapsulate(int from, int to, String algorithm);

}

public Encapsulator newEncapsulator(PublicKey pk)

throws InvalidKeyException;

public Encapsulator newEncapsulator(PublicKey pk, SecureRandom sr)

throws InvalidKeyException;

public Encapsulator newEncapsulator(PublicKey pk, AlgorithmParameterSpec spec,

SecureRandom sr)

throws InvalidAlgorithmParameterException, InvalidKeyException;

public static final class Decapsulator {

String providerName();

int secretSize(); // Size of the shared secret

int encapsulationSize(); // Size of the key encapsulation message

SecretKey decapsulate(byte[] encapsulation) throws DecapsulateException;

SecretKey decapsulate(byte[] encapsulation, int from, int to,

String algorithm) throws DecapsulateException;

}

public Decapsulator newDecapsulator(PrivateKey sk)

throws InvalidKeyException;

public Decapsulator newDecapsulator(PrivateKey sk, AlgorithmParameterSpec spec)

throws InvalidAlgorithmParameterException, InvalidKeyException;

}

The

getInstancemethods create a newKEMobject that implements the specified algorithm.

And here is an example of how to use this class (again, taken from the JEP):

// Receiver side

KeyPairGenerator g = KeyPairGenerator.getInstance("ABC");

KeyPair kp = g.generateKeyPair();

publishKey(kp.getPublic());

// Sender side

KEM kemS = KEM.getInstance("ABC-KEM");

PublicKey pkR = retrieveKey();

ABCKEMParameterSpec specS = new ABCKEMParameterSpec(...);

KEM.Encapsulator e = kemS.newEncapsulator(pkR, specS, null);

KEM.Encapsulated enc = e.encapsulate();

SecretKey secS = enc.key();

sendBytes(enc.encapsulation());

sendBytes(enc.params());

// Receiver side

byte[] em = receiveBytes();

byte[] params = receiveBytes();

KEM kemR = KEM.getInstance("ABC-KEM");

AlgorithmParameters algParams = AlgorithmParameters.getInstance("ABC-KEM");

algParams.init(params);

ABCKEMParameterSpec specR = algParams.getParameterSpec(ABCKEMParameterSpec.class);

KEM.Decapsulator d = kemR.newDecapsulator(kp.getPrivate(), specR);

SecretKey secR = d.decapsulate(em);

// secS and secR will be identical

What’s Different From Java 20?

The Key Encapsulation Mechanism API didn’t exist yet in Java 20; it was newly added in Java 21.

More Information

There is a bit more to this API than we were able to cover here (like different KEM configurations, for example), so to get the full picture you could have a look at JEP 452.

Final thoughts

Phew! I guess it’s safe to say that JDK 21 turned out to be quite the update, with no less than 15 JEPs delivered! And that’s not even all that’s new: thousands of other updates were included in this new release, including various performance and stability updates. Our favourite language is clearly more alive than ever, and I think it’s due to Java’s continuing focus on its best traits: performance, stability, security, compatibility and maintainability. Wishing you many happy hours of developing with Java 21!